Scar formation: what it is and what you can do about it

Scars are your skin’s way of repairing itself after an injury. They may look stubborn, but you can influence how they form and how they fade. The key is smart care early on and sensible treatments later.

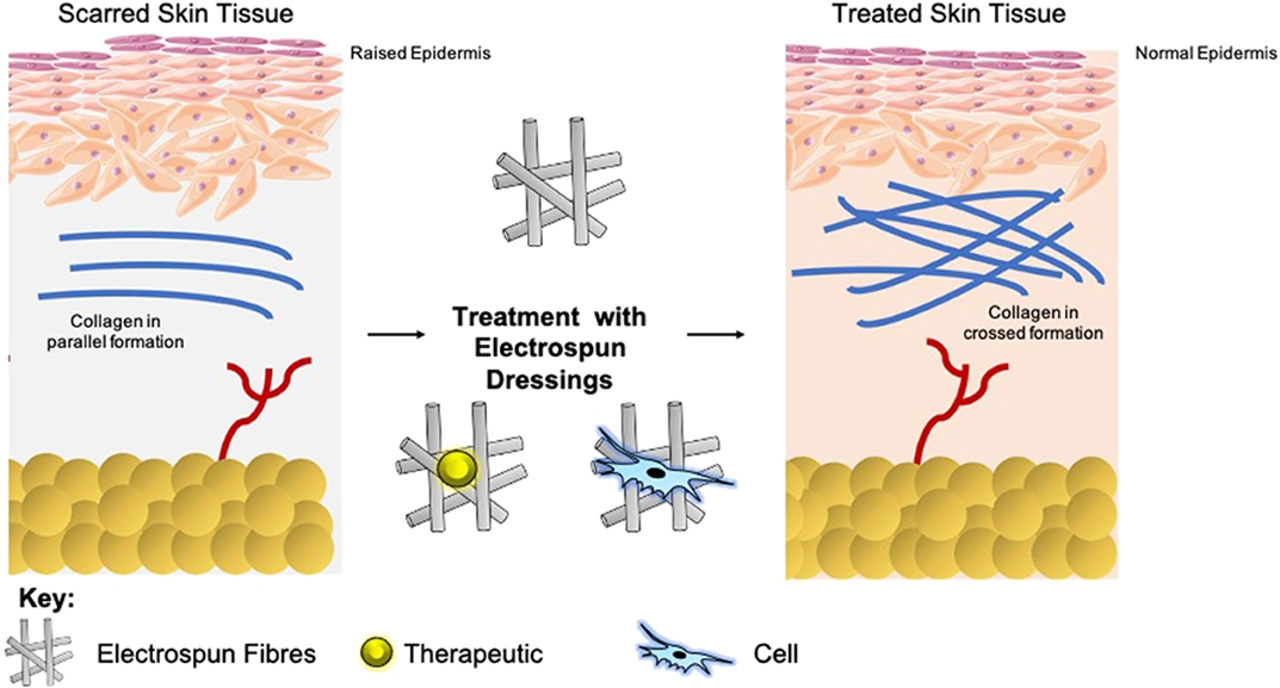

When you cut or burn the skin, the body builds new collagen to close the gap. That new tissue isn’t identical to the original — that’s why scars can be flat, sunken, red, or raised. The type of scar you get depends on how deep the wound was, where it happened, your age, and your genes. Darker skin tones and some families are more likely to form raised scars called keloids.

Immediate care that really helps

What you do in the first days matters more than most people realize. Clean the wound gently with soap and water. Stop bleeding with light pressure. If the cut needs stitches, see a clinician — well-placed stitches can mean a smaller scar.

Once the wound is closed, keep it moist and covered. Apply petroleum jelly or a recommended ointment and use a non-stick dressing. Moist healing reduces scab formation and leads to thinner scars. And don’t pick at scabs — that’s one of the quickest ways to make a scar worse.

Avoid direct sun on new scars. UV exposure darkens scars and makes them more visible for months. Use an SPF 30+ sunscreen or cover the area for at least the first year while the scar is maturing.

How to treat scars after they form

Give a new scar time — most change a lot during the first 6–12 months. For early, visible improvement, try silicone gel or silicone sheets. These are proven to soften and flatten scars if used consistently for weeks to months. Massage the scar for a few minutes a day with a gentle cream once the wound is fully closed; massage can help break down tight collagen.

If a scar becomes thick, red, itchy, or keeps growing beyond the original wound, it could be hypertrophic or a keloid. Treatments that work for those include steroid injections, laser therapy, and pressure therapy. These need a dermatologist or specialist, so book an appointment rather than trying strong treatments at home.

For acne or pitted scars, options include topical retinoids, chemical peels, microneedling, and lasers — again, best discussed with a dermatologist. Over-the-counter creams can help slightly, but medical procedures usually give bigger changes.

Watch for infection (increasing redness, warmth, pus, or fever) and get medical help if those appear. If a scar is painful, keeps growing, or affects movement (near a joint), talk to a doctor early — treating it sooner gives better results.

Small, steady steps work best: clean and protect wounds, use silicone and sunscreen, try gentle massage, and see a pro for stubborn or abnormal scars. If you want product suggestions, your pharmacist can point to reliable gels, sheets, and sunscreens suited to your skin.