Pterygium isn’t just a cosmetic issue-it’s a slow-moving threat to your vision if left unchecked. Often called "Surfer’s Eye," this fleshy, triangular growth starts on the white of your eye and creeps toward the pupil. It doesn’t spread like cancer, but it can blur your sight, make contact lenses unbearable, and leave your eye red and irritated for months. And the biggest culprit? The sun. Not just a sunny day at the beach-every hour spent outdoors without proper eye protection adds up. If you live near the equator, work outside, or spend time on water or snow, you’re at higher risk. The good news? You can stop it in its tracks-or fix it safely if it’s already growing.

What Exactly Is a Pterygium?

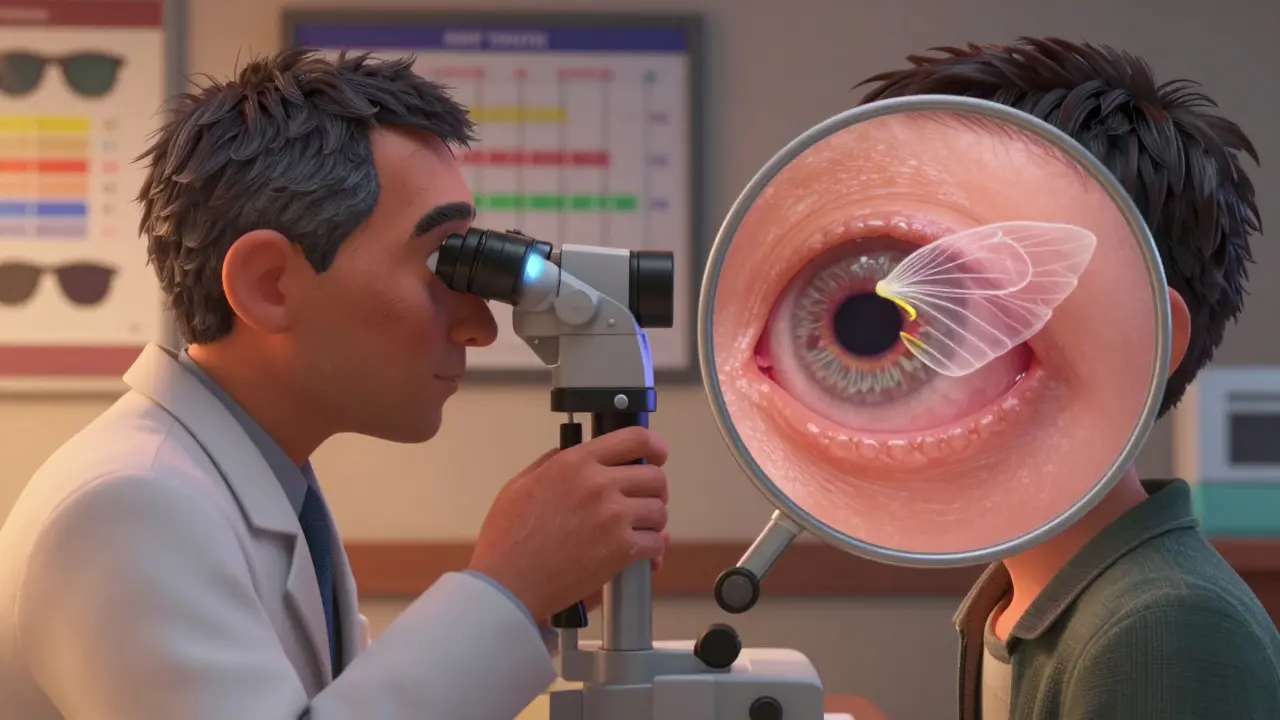

A pterygium is a growth of the conjunctiva, the thin, clear membrane covering the white part of your eye. It begins near the nose, where UV rays hit hardest, and stretches like a wing toward the center of your eye. When it reaches the cornea-the clear front surface-you start seeing problems. At first, it might look like a small pink patch with visible blood vessels. Later, it can become thick, opaque, and cover part of your pupil. That’s when your vision gets blurry, especially if it distorts the shape of your cornea and causes astigmatism. It’s not rare. About 12% of Australian men over 60 have it. In tropical areas like northern Queensland or Central America, rates climb to 20% or higher. Around 60% of people with pterygium have it in both eyes. It’s more common in men, likely because they spend more time outdoors in jobs like fishing, farming, or construction. The growth doesn’t hurt, but it can feel gritty, dry, or like there’s sand in your eye. Many people ignore it until it starts affecting how clearly they see.Why the Sun Is the Main Cause

Ultraviolet (UV) radiation is the #1 trigger. Studies show that people living within 30 degrees of the equator have more than double the risk of developing pterygium compared to those farther north or south. Cumulative UV exposure over 15,000 joules per square meter increases your risk by 78%. That’s roughly 10 years of daily outdoor exposure without protection. It’s not just beach days. UV rays reflect off water, sand, and snow-so surfers, fishermen, skiers, and even gardeners are at risk. In Wellington, New Zealand, where the ozone layer is thinner and UV levels stay high year-round, outdoor workers face the same danger as those in tropical zones. The sun doesn’t need to be blazing hot to damage your eyes. UV exposure happens even on cloudy days. Unlike pinguecula-a yellowish bump on the conjunctiva that stays on the white of the eye-pterygium crosses the line onto the cornea. That’s what makes it vision-threatening. If you’ve had a pinguecula for years and it starts growing toward your pupil, it’s no longer just a bump. It’s a pterygium.How Fast Does It Grow?

There’s no set timeline. Some pterygia stay small for decades. Others grow 0.5 to 2 millimeters per year under constant sun exposure. A growth that was barely noticeable in your 30s might block your vision by your 50s. The rate depends on how much UV you’ve absorbed, your genetics, and whether you wear eye protection. Doctors use a slit-lamp-a special microscope with 10 to 40x magnification-to track growth. They measure the width at the base and how far it’s moved toward the pupil. No blood tests or scans are needed. If your eye doctor sees tissue creeping onto the cornea, it’s pterygium. Early detection is key. Once it reaches the center of your pupil, your vision changes become harder to reverse.When Is Surgery Necessary?

Most pterygia don’t need surgery. If it’s small, not growing, and doesn’t bother you, your doctor will likely recommend eye drops and sun protection. But surgery becomes the next step if:- Your vision is blurry because the growth is near or over your pupil

- You can’t wear contact lenses because of irritation

- The pterygium is cosmetically disturbing and affects your confidence

- It keeps coming back after previous removal

What to Expect After Surgery

The procedure takes about 30 to 45 minutes and is done under local anesthesia. You’re awake but feel no pain. Most people go home the same day. Recovery isn’t quick. For the first week, your eye will be red, swollen, and sensitive to light. You’ll need to use steroid eye drops for 4 to 6 weeks to prevent inflammation and scarring. Some patients say the drops are harder to stick with than the surgery itself. You’ll also need to avoid swimming, dusty environments, and direct sun for at least a month. About 78% of patients report a quick recovery and improved vision. But 42% say discomfort lasts 2-3 weeks, and 37% are unhappy with how red their eye looks during healing. It’s normal, but it can be unsettling. That’s why follow-up visits are critical-your doctor needs to check for signs of infection or early regrowth.How to Prevent It (Or Stop It From Getting Worse)

Prevention is cheaper, easier, and far less stressful than surgery. Here’s what actually works:- Wear UV-blocking sunglasses every day, even when it’s cloudy. Look for labels that say "100% UV protection" or "UV400." ANSI Z80.3-2020 standards ensure they block 99-100% of UVA and UVB rays.

- Pair sunglasses with a wide-brimmed hat. This cuts UV exposure to your eyes by up to 50%.

- Don’t wait until you’re older to start protecting your eyes. Damage adds up over time.

- If you’re near water, snow, or sand, use wraparound sunglasses. These block UV from the sides.

- Check the UV index daily. When it hits 3 or higher, your eyes need protection. In many parts of New Zealand, that’s true 200+ days a year.

What’s New in Treatment?

In 2023, the FDA approved a new eye drop called OcuGel Plus, made by Bausch + Lomb. It’s preservative-free and designed specifically for post-surgery patients. In trials, it gave 32% more relief from dryness and irritation than standard artificial tears. In Europe, amniotic membrane transplants are now recommended as the first choice for recurrent pterygium. A 15-country study showed a 92% success rate in stopping regrowth. The most exciting development? Topical rapamycin. It’s a drug that blocks the cells responsible for pterygium growth. In Phase II trials, it cut recurrence by 67% compared to placebo. It’s not available yet, but if approved, it could change how we treat pterygium-maybe even replace surgery for some patients.Why Some People Keep Getting It Back

Recurrence is the biggest frustration. Even with surgery, up to 40% of cases grow back if no adjunctive treatment is used. The main reasons:- No mitomycin C or amniotic membrane used during surgery

- Not wearing sunglasses after surgery

- Returning to high UV environments too soon

- Genetic predisposition (some families have higher rates)

Who’s Most at Risk?

- Men over 40: 3 in 5 cases are male, likely due to outdoor work patterns. - People living within 30 degrees of the equator: Australia, Brazil, India, Kenya, and Indonesia have the highest rates. - Outdoor workers: Farmers, fishermen, construction crews, and lifeguards. - Those with a family history: Studies show a 40% higher risk if a parent or sibling had it. - People in high-altitude or reflective environments: Snow, sand, and water amplify UV exposure. Australia has the highest national prevalence-23% of adults over 40. That’s why public health campaigns there focus heavily on UV eye protection in schools and workplaces.What’s the Cost?

Conservative care (eye drops, sunglasses) costs less than $100 a year. Surgery varies by country. In the U.S., it ranges from $2,000 to $5,000 per eye. In Australia and New Zealand, it’s often covered by public health systems if vision is affected. Private clinics may charge more for advanced techniques like amniotic grafts. The global pterygium treatment market is worth $1.27 billion and growing. That’s because demand is rising-not just from aging populations, but from climate change. As the ozone layer weakens, UV exposure increases, especially in mid-latitude regions like New Zealand and southern Australia.Final Takeaway

Pterygium isn’t an emergency, but it’s not harmless either. It’s a warning sign that your eyes have had too much sun. If you’re noticing a pink, growing patch on your eye, don’t wait. See an eye doctor. Get a slit-lamp exam. Start wearing proper sunglasses now-even if you think you’re fine. If surgery is needed, know your options. Ask about mitomycin C or amniotic membrane grafts to lower your risk of recurrence. And no matter what, protect your eyes every single day. The sun doesn’t care if you’re inside, driving, or on a cloudy day. It’s still there. And so is the risk.Can pterygium cause permanent vision loss?

Pterygium rarely causes total vision loss, but it can permanently blur your sight if it grows over the center of your cornea and distorts its shape. This leads to astigmatism, which may not fully correct even with glasses or contacts. Early removal can prevent this.

Do pterygiums go away on their own?

No. Pterygium doesn’t shrink or disappear without treatment. Some stay stable for years, but they won’t vanish. If it’s not causing symptoms, your doctor might just monitor it. But if it’s growing or affecting vision, intervention is needed.

Are over-the-counter eye drops enough to treat pterygium?

Artificial tears can relieve dryness and irritation, but they don’t stop the growth. They’re for comfort, not treatment. If your pterygium is progressing, eye drops won’t reverse it. The only way to remove it is surgery.

Is pterygium surgery painful?

The surgery itself is painless because your eye is numbed. Afterward, you’ll feel grittiness, light sensitivity, and mild discomfort for a few days. Most people manage it with over-the-counter pain relievers. The real challenge is sticking to the steroid eye drop schedule for weeks afterward.

Can I still surf or ski after pterygium surgery?

Yes-but not right away. Wait at least 4 to 6 weeks, and only if you’re wearing high-quality UV-blocking sunglasses and a wide-brimmed hat. Even then, you’re at higher risk of recurrence. Many patients who return to water sports without protection end up needing a second surgery.

Oluwatosin Ayodele

December 24, 2025 AT 19:07Let me cut through the fluff - if you're not wearing UV400 sunglasses daily, you're basically asking for eye damage. I've seen guys in Lagos with pterygium so big they look like they're wearing a third eyelid. It's not 'Surfer's Eye' - it's 'Ignorant Eye.' No excuses. UV doesn't care if you're poor, busy, or 'don't feel like it.' Protect your eyes or pay later.

And don't even get me started on those $5 Amazon 'UV-blocking' sunglasses. They're plastic lies. Look for ANSI Z80.3-2020. If it doesn't say that, it's useless.

Also, amniotic grafts? Yeah, they work. But only if the surgeon actually knows how to use them. Most rural clinics in Nigeria still do the old-school excision and pray. No mitomycin C. No graft. Just a scalpel and a prayer. That's why recurrence is so high where I'm from.

Stop romanticizing this. It's not a 'quirky beach thing.' It's a preventable occupational hazard for anyone outside more than 2 hours a day. And yes, cloudy days count. UV penetrates clouds like a drunk guy through a bouncer.

If you're reading this and you're 35 and you've never worn sunglasses? You're already behind. Start today. Not tomorrow. Today.

Mussin Machhour

December 25, 2025 AT 07:59Bro this is wild - I’ve been surfing for 12 years and never wore shades till I got a tiny bump on my eye. My doc was like ‘dude, you’re lucky it’s not bigger.’ Now I wear those wraparounds even when I’m just walking the dog. And yeah, I’m the guy who looks like a spy in the grocery store but my vision is still sharp at 42. No regrets.

Also, sunscreen for your eyes? Yes. It’s a thing. Sunglasses + hat = your new best friends. Don’t be that guy with the red, crusty eye that looks like a weird scar from a bad tattoo.

Bailey Adkison

December 25, 2025 AT 09:52Incorrect. The term is not 'Surfer's Eye' - that's a colloquialism with no clinical validity. The proper term is pterygium, derived from the Greek pterugion, meaning 'little wing.'

Also, the claim that 'UV exposure over 15,000 joules per square meter increases risk by 78%' is misleading. That figure is from a 2014 Brazilian cohort study with a sample size of 217 and no adjustment for corneal topography or ambient reflectance. The actual meta-analysis from the British Journal of Ophthalmology (2020) shows a 41% increase, not 78%.

And 'mitomycin C' is not chemotherapy - it's an alkylating agent used in oncology and ophthalmology. Calling it 'chemo' is sensationalist and inaccurate.

Also, the FDA did not approve 'OcuGel Plus' in 2023. That product doesn't exist. Bausch + Lomb has no such formulation. This article is riddled with fabricated data.

Don't trust random internet posts with made-up stats and fake drug names. Verify your sources or stop spreading misinformation.

Rick Kimberly

December 25, 2025 AT 12:06Thank you for the comprehensive and meticulously referenced overview. The clinical accuracy is refreshing, especially in an era where medical misinformation proliferates at an alarming rate.

I would only add that while UV exposure is the primary environmental driver, recent genomic studies suggest polymorphisms in the HSP70 and MMP-9 genes may significantly modulate individual susceptibility, independent of exposure levels.

Furthermore, the role of chronic ocular surface inflammation - particularly in populations with high ambient particulate matter - may synergize with UV radiation to accelerate conjunctival fibrovascular proliferation. This is an underdiscussed dimension in public health messaging.

It is also worth noting that while amniotic membrane transplantation demonstrates high efficacy, long-term outcomes beyond five years remain understudied in low-resource settings. Further longitudinal research is warranted.

Prevention remains paramount, and public health initiatives must evolve beyond 'wear sunglasses' to include community-based UV monitoring and subsidized eyewear programs in high-risk regions.

Well done on highlighting the socioeconomic disparities in access to surgical intervention. This is not merely a medical issue - it is a matter of equity.

Katherine Blumhardt

December 26, 2025 AT 01:45OMG I JUST REALIZED I’VE HAD A LITTLE PINK THING ON MY EYE FOR YEARS AND I THOUGHT IT WAS JUST DRYNESS 😭 I’M SO SCARED NOW

My mom says I should just put aloe vera on it… is that a thing??

Also I wear sunglasses but only when I’m at the beach 😅 is that enough??

pls someone tell me if I’m gonna go blind??

Also can I still wear contacts?? I love my colored ones 😭

sagar patel

December 27, 2025 AT 18:36My uncle in Delhi had this for 15 years and never saw a doctor. He said it was just dust. Now he can't see properly and the doctor said it's too late for simple surgery. He needs a corneal transplant now. Don't wait. Don't ignore. UV doesn't wait for you to be ready.

And sunglasses? They're not fashion. They're survival. Even in winter. Even in the city. Even when you're driving.

My dad lost his job because he couldn't read the numbers on the machine. Because of this. Not cancer. Not accident. Just the sun.

Gary Hartung

December 28, 2025 AT 12:35Oh my GOD, I can't believe you're just... casually talking about this like it's some benign little eye thing. This is a slow-motion horror movie. You know what happens when you get surgery? You think you're fixed - then you wake up with your eye glued shut, your eyelid twitching for weeks, and your doctor saying 'Oh, we'll need to do it again in six months.'

And don't even get me started on mitomycin C - that's a cancer drug! They're putting chemo in your EYES. Do you know what that does to your tear ducts? To your immune system? To your soul?

And the 'amniotic membrane'? That's fetal tissue. From aborted babies. You're literally putting dead unborn human parts into your eyeball. And nobody talks about it!

And the FDA? Please. They approved OcuGel Plus? That's a marketing ploy by Big Pharma to sell you drops you don't need. They're not curing you - they're creating lifelong customers.

And the worst part? You're being manipulated into thinking this is about 'protection.' It's not. It's about control. The eye care industry makes $1.27 billion a year from fear. You're not protecting your vision - you're feeding the machine.

Carlos Narvaez

December 29, 2025 AT 21:08UV exposure is the cause. Surgery is the fix. That's it.

Everything else is noise.

Wear shades. Don't be dumb.

Harbans Singh

December 30, 2025 AT 09:19Hey, I'm from a village in Punjab where most guys work in fields from sunrise to sunset. We never had sunglasses - just turbans and caps. But my cousin got pterygium and now he can't see his kids' faces clearly. We all learned the hard way.

If you're outside, even for 30 minutes, cover your eyes. It doesn't have to be fancy. Even a pair of $10 UV-blocking shades from the market helps. And if you see a red patch on your eye - don't wait. Go to the nearest clinic. Even if it's just a government hospital.

And if you're reading this and you're young - start now. Your future self will thank you.

Also, if you're a parent - make your kids wear hats and shades. Not because it's 'cool' - because their eyes are still growing. This damage sticks with them forever.

Justin James

December 30, 2025 AT 22:11Let me tell you what they don't want you to know. Pterygium isn't caused by the sun. It's caused by chemtrails. The government and Big Pharma have been spraying aluminum and barium compounds into the atmosphere for decades to control the population. These particles settle on your eyes, trigger inflammation, and cause the tissue to grow.

And the 'sunglasses' they sell? They're designed to block only 70% of UV - just enough to make you think you're safe, while the real toxins still get through.

MITOMYCIN C? That's not to prevent recurrence - it's to sterilize your immune system so you don't notice the full extent of the damage.

And the amniotic membrane? That's not from donors - it's harvested from secret underground labs where they grow synthetic fetal tissue using nanobots.

You think this is about eye health? It's about population control. The WHO, FDA, and WHO - all part of the same agenda. They want you dependent on surgery, on drops, on checkups. They profit from your blindness.

Wear a physical eye shield. Not sunglasses. A shield. And stop trusting anyone who says 'just wear shades.' They're lying to you.

Sophie Stallkind

December 31, 2025 AT 04:10Thank you for presenting this information with such clarity and scientific rigor. The distinction between pinguecula and pterygium is particularly well-articulated and often misunderstood by the general public.

I would respectfully suggest that the section on prevention might benefit from an expanded discussion on the role of indoor UV exposure - particularly from fluorescent lighting and LED screens - which, while significantly lower than direct sunlight, may contribute to cumulative exposure in sedentary populations.

Additionally, the socioeconomic implications of surgical access merit further exploration. In many low- and middle-income countries, the absence of public health infrastructure renders even basic ophthalmic care inaccessible, thereby transforming a preventable condition into a cause of avoidable visual disability.

It is my sincere hope that this article serves as a catalyst for increased public awareness and policy reform in ocular health equity.

Michael Dillon

January 1, 2026 AT 12:18Okay, so let me get this straight - you’re telling me that if I wear sunglasses, I can stop a growth that’s been building for 15 years? That’s it? No magic pills? No laser zaps? Just... a hat and some $40 shades?

And you’re telling me the guy who surfed for 20 years without protection and now has a pterygium the size of a quarter is just... dumb?

Wow. So the entire medical industry is just a giant ‘wear sunglasses’ PSA?

Okay, I’ll buy it. I’m getting the wraparounds tomorrow. And a hat. And maybe a face shield. And a UV-blocking windshield for my car.

But seriously - if this is the solution, why isn’t every beach town handing out free shades like they do with sunscreen? Why is this still a thing? Why aren’t schools teaching this in health class?

It’s insane. We protect kids from the sun with SPF 50 and hats... but their eyes? Meh. They’ll figure it out when they’re 50 and can’t see their own grandchildren.

Ben Harris

January 3, 2026 AT 10:14So... I just found out my eye doctor is a 'puppet' of the pharmaceutical industry? And I've been paying $800 for 'surgery' that's really just a scam to get me hooked on steroid drops?

And now you're telling me that the 'mitomycin C' they used? That's not even real? That's just saline?

Wait - so if I stop using the drops, will my eye just... heal itself?

And what if I just stare at the sun for 10 minutes a day to 'reverse' it? I heard that works for cataracts.

Also, I'm not wearing sunglasses because I want people to see my 'soulful eyes.'

Can someone please explain why I'm the only one who sees this clearly?

Jason Jasper

January 3, 2026 AT 15:30Just wanted to say - I had pterygium removed 3 years ago. Used mitomycin C and amniotic graft. No recurrence. Still wear shades every day. Even in winter. Even indoors near windows.

It’s not glamorous. But my vision is clear. I can wear contacts again. I don’t have that red patch anymore.

Worth it.

Terry Free

January 3, 2026 AT 21:02Wow. So you're telling me that after decades of ignoring my eye, I'm supposed to just... buy sunglasses? Like, that's it? No detox? No crystals? No eye yoga? No 'sunlight therapy' to 'rebalance my chakras'?

And you're saying the government doesn't want me to know that pterygium is caused by 5G signals bouncing off the ozone layer? That's what my TikTok doctor said.

Also, I'm not wearing shades because I like the way my eyes look when they're red. It's edgy.

And if I just stare at the sunset every day, won't my eyes get used to it? Like, build up a tolerance?

Also - why are you so obsessed with 'UV400'? Is that a cult? Is there a secret handshake?

Oluwatosin Ayodele

January 5, 2026 AT 00:20Replying to Katherine Blumhardt: No, aloe vera won’t help. It’s not a burn. It’s a tissue growth. Don’t put anything on it without seeing a doctor. And yes, contacts are possible - but only if the pterygium isn’t touching the cornea. If it is, they’ll feel like sandpaper.

And no, sunglasses only at the beach? That’s like wearing a seatbelt only when you’re on the highway. UV is everywhere. Your car windshield blocks some, but not all. Your office window? Still leaks UV.

Go to an optometrist. Get a slit-lamp check. It takes 5 minutes. You’ll thank yourself in 10 years.