When a pharmacist swaps a brand-name drug for a generic version, it looks like a simple win: cheaper for patients, cheaper for insurers. But behind that swap is a tangled financial system that can actually hurt pharmacies, confuse patients, and sometimes cost more than it saves. This isn’t about whether generics work-they do. It’s about how we pay for them, and who really benefits.

How Pharmacies Get Paid for Generics

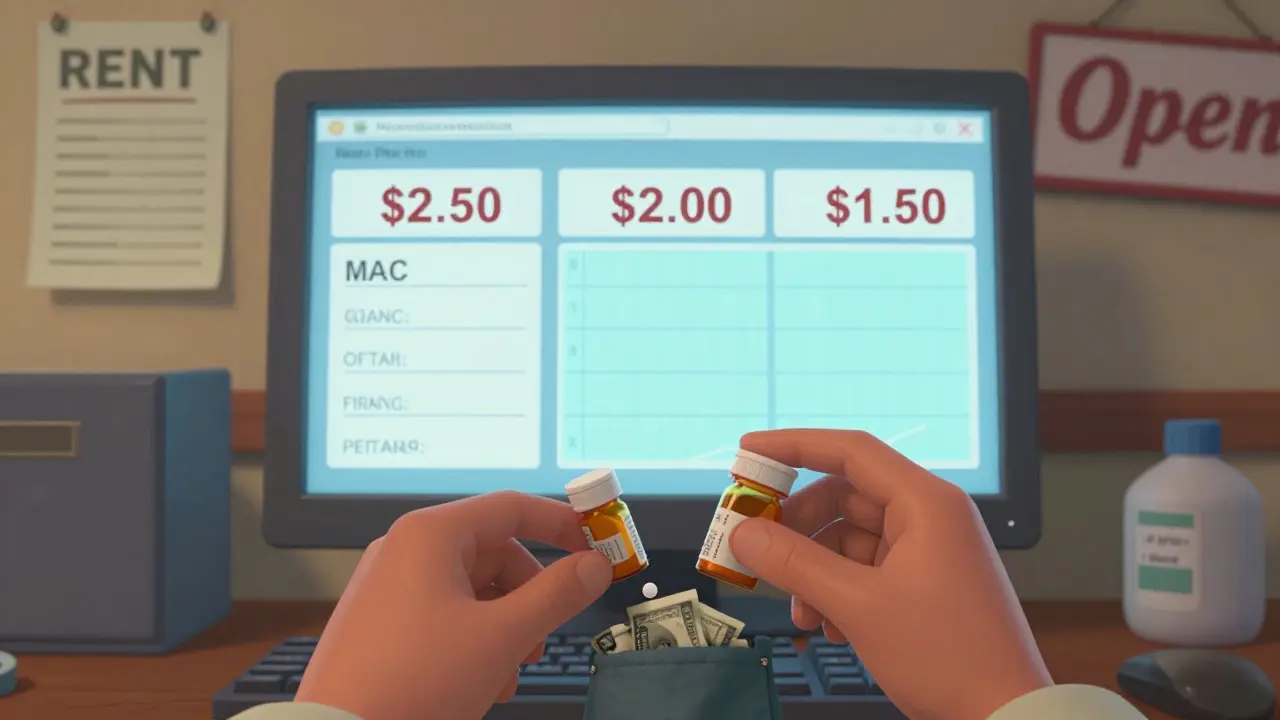

Pharmacies don’t get paid the same way for every drug. For brand-name drugs, reimbursement used to be based on the Average Wholesale Price (AWP)-a list price that often had little to do with what the pharmacy actually paid. Today, most generic drugs are paid for using Maximum Allowable Cost (MAC) lists. These are secret price caps set by Pharmacy Benefit Managers (PBMs) that tell pharmacies the most they’ll get reimbursed for a generic drug.

Here’s the catch: MAC lists aren’t standardized. One PBM might pay $2.50 for a 30-day supply of lisinopril, while another pays $5.50 for the same pill. The pharmacy might have bought it for $1.80, but if the MAC is $2.50, they only make 70 cents. If the MAC drops to $2.00? They lose money. That’s why many independent pharmacies now stock fewer generics-they can’t afford to lose on every fill.

On top of that, pharmacies get a flat dispensing fee-usually $5 to $12 per prescription-no matter the drug’s cost. That fee hasn’t kept up with inflation, while operating costs have soared. So even though generics have a 42.7% gross margin on average (compared to just 3.5% for brand-name drugs), many pharmacies barely break even after rent, staff, and compliance costs.

The PBM Profit Machine

Pharmacy Benefit Managers-CVS Caremark, Express Scripts, OptumRx-control about 80% of prescription claims in the U.S. They’re supposed to negotiate lower prices. But instead, many make money through something called spread pricing.

Here’s how it works: A PBM tells a pharmacy they’ll pay $3 for a generic drug. The pharmacy buys it for $1.75. But the PBM charges the insurer or employer $6. The $4.25 difference? That’s the spread. And it’s hidden from the patient and the plan sponsor. The higher the MAC, the bigger the spread. So PBMs have a financial incentive to keep MACs high-even if a cheaper generic exists.

Studies show that when PBMs switch patients to a higher-priced generic in the same class, the price difference can be over 20 times more than the cheapest alternative. Why? Because the PBM pockets the difference. A patient might think they’re saving money by switching to a generic, but if the PBM picks the most expensive version, the real savings go to the middleman-not the patient or the pharmacy.

Therapeutic Substitution: The Real Savings Opportunity

Most people think generic substitution means swapping one brand for its generic version. But the real cost savings come from therapeutic substitution-switching to a completely different drug that works just as well but costs far less.

For example, instead of switching from brand-name Lipitor to generic atorvastatin, a better move might be switching from atorvastatin to rosuvastatin, which can be 70% cheaper in some markets. The Congressional Budget Office found that in 2007, switching just seven types of brand-name drugs to lower-cost alternatives saved $4 billion. Switching between generic versions? Only $900 million.

But PBMs rarely push therapeutic substitution. Why? Because it’s harder to control. MAC lists are built around specific drug names, not therapeutic classes. If a PBM wants to maximize spread, they need to stick to one drug they can mark up. That’s why pharmacists often can’t recommend the cheapest option-even if it’s clinically better.

Why Independent Pharmacies Are Disappearing

Since 2018, over 3,000 independent pharmacies have closed. That’s not because people stopped filling prescriptions. It’s because reimbursement has become a race to the bottom.

Big chains like Walgreens and CVS have leverage. They negotiate directly with PBMs and get better MAC rates. Independent pharmacies? They take whatever’s offered. Many are forced to fill prescriptions at a loss just to stay in the network. One pharmacist in Wisconsin told me she lost $1.20 on every generic prescription she filled last year. She made it up on over-the-counter sales.

When pharmacies can’t afford to stock certain drugs, patients suffer. A diabetic might need a specific insulin pen, but if the MAC is too low, the pharmacy doesn’t carry it. The patient has to drive 30 miles to another pharmacy-or skip the dose.

What’s Changing? Regulations and Pressure

There’s growing pressure to fix this. The Federal Trade Commission is investigating PBM spread pricing. Fifteen states now have Prescription Drug Affordability Boards that set Upper Payment Limits (UPLs)-essentially caps on how much insurers can be charged for certain drugs. These rules are pushing PBMs to use cheaper generics.

The Inflation Reduction Act of 2022 started forcing Medicare Part D to disclose pricing. That transparency might spill over into commercial plans. If patients and employers can see what PBMs are really charging, the hidden spreads won’t last.

Some insurers are starting to pay pharmacies based on the actual cost of the drug plus a fair dispensing fee-what’s called cost-plus reimbursement. It’s simple: pay what the pharmacy paid, plus a fixed fee. No spreads. No MAC games. But PBMs hate it. It cuts their profits.

What This Means for Patients

Patients think generics are always cheaper. But sometimes, they’re not. A $5 copay on a generic might still cost the insurer $15-because of spread pricing. And if the pharmacy doesn’t have the cheapest version in stock, you might end up with a more expensive one by default.

Ask your pharmacist: "Is there a lower-cost generic in this class?" They might know about a $1.50 alternative you didn’t know existed. And if your insurer won’t cover it, ask them why. You might be surprised.

It’s not about avoiding generics. It’s about making sure the system rewards the right choices. When reimbursement aligns with true cost savings-not PBM profits-everyone wins: patients pay less, pharmacies stay open, and the system actually works.

Yuri Hyuga

January 21, 2026 AT 04:22Wow. This is the kind of post that makes you realize how broken the system really is. 🤯 I never thought about how PBMs profit from the gap between what they pay pharmacies and what they charge insurers. It’s not just about generics-it’s about who controls the money flow. And honestly? It’s criminal that pharmacists are losing money just trying to help people. We need transparency, now. 💪

Coral Bosley

January 23, 2026 AT 03:48This whole thing is a goddamn scam. I’ve seen my grandma pay $40 for a generic pill while the insurance paid $120-and the pharmacy got nothing. They’re not saving anyone money. They’re just moving the loot around like a magic trick with a middleman in a suit.

Steve Hesketh

January 24, 2026 AT 15:02Let me tell you something-I work in a community pharmacy in Lagos, and even though we don’t have PBMs here, the same pain echoes. When the cost of medicine goes up but the reimbursement stays flat, we’re forced to choose: feed our staff or feed our shelves. This isn’t just an American problem. It’s a global crisis of care. We’re not just selling pills-we’re holding up health systems with our own pockets. And nobody’s thanking us. 🙏

Philip Williams

January 26, 2026 AT 04:39The data presented here is compelling, particularly the distinction between generic substitution and therapeutic substitution. The Congressional Budget Office figures suggest that systemic reform should prioritize therapeutic equivalence over brand-to-generic transitions. This implies that formulary design, not merely MAC lists, requires re-engineering to incentivize true cost reduction. Further, the stagnation of dispensing fees relative to operational inflation represents a structural failure in reimbursement modeling.

Ben McKibbin

January 26, 2026 AT 11:01Let’s be real: PBMs are parasites. They don’t add value-they extract it. And the fact that independent pharmacies are being driven out by this rigged system? That’s not capitalism. That’s corporate feudalism. The FTC needs to break them up, not investigate them. And Congress? Stop pretending they care about patients. Pass cost-plus reimbursement now. No more delays. No more excuses. The pharmacy on your corner is dying because of greed disguised as efficiency.

Melanie Pearson

January 28, 2026 AT 08:20It is entirely predictable that the erosion of pharmaceutical reimbursement margins would lead to the decline of independent retail outlets. This phenomenon is not a failure of policy, but rather a natural consequence of market forces favoring economies of scale. The notion that PBMs are somehow 'exploitative' is a romanticized mischaracterization. Profit motives drive innovation. If independent pharmacies cannot compete, they should exit the market. Sentimentality has no place in healthcare economics.

Rod Wheatley

January 28, 2026 AT 14:38Okay, I’ve been a pharmacist for 22 years, and this? This is EXACTLY what we’ve been screaming about. We get paid $6.50 to fill a script, but rent is $8,000 a month. Staff salaries? Up 18% since 2020. Insurance copays? Still $5 for everything. And PBMs? They’re laughing all the way to the bank while we’re counting pennies to pay the electric bill. I’ve filled prescriptions at a loss for five years straight. I don’t do it for the money. I do it because someone’s gotta be there when the kid with asthma needs his inhaler at 10 p.m. But I can’t keep doing this forever. Nobody’s talking about the human cost here.

Uju Megafu

January 29, 2026 AT 11:50Oh, so now it’s the pharmacist’s fault? No. It’s the fault of lazy patients who don’t ask questions. It’s the fault of insurers who outsource everything to middlemen. It’s the fault of politicians who take PBM donations. And it’s the fault of you-yes, YOU-for not demanding transparency. You think your $5 copay is a deal? It’s a trap. You’re paying more than you think, and you’re letting them get away with it. Wake up. This isn’t healthcare. It’s a casino. And you’re the sucker.

Jarrod Flesch

January 30, 2026 AT 15:09Man, this hits hard. 😔 I used to work in a small-town pharmacy in Tasmania. We’d give out free samples just to keep people alive. One old bloke came in every week for his blood pressure med-we knew his name, his dog’s name, and that he’d skip doses if the price went up. We lost money on every script, but we kept him coming back. The system’s broken, but we’re still here. Maybe that’s the real win. 🙌

Kelly McRainey Moore

January 31, 2026 AT 02:18My mom’s a nurse, and she told me about a patient who drove 90 minutes because her local pharmacy didn’t stock the cheapest generic. That’s not healthcare. That’s a logistical nightmare. I’m going to send this post to my rep. We need change, and we need it yesterday.