When a mother takes a medication while breastfeeding, it’s natural to wonder: is my baby getting this drug too? The answer is yes - but not always in a way that matters. Most medications pass into breast milk in tiny amounts, and even fewer cause any harm. The real issue isn’t whether drugs get into milk - it’s understanding which ones do, how much, and what that actually means for your baby’s health.

How Medications Get Into Breast Milk

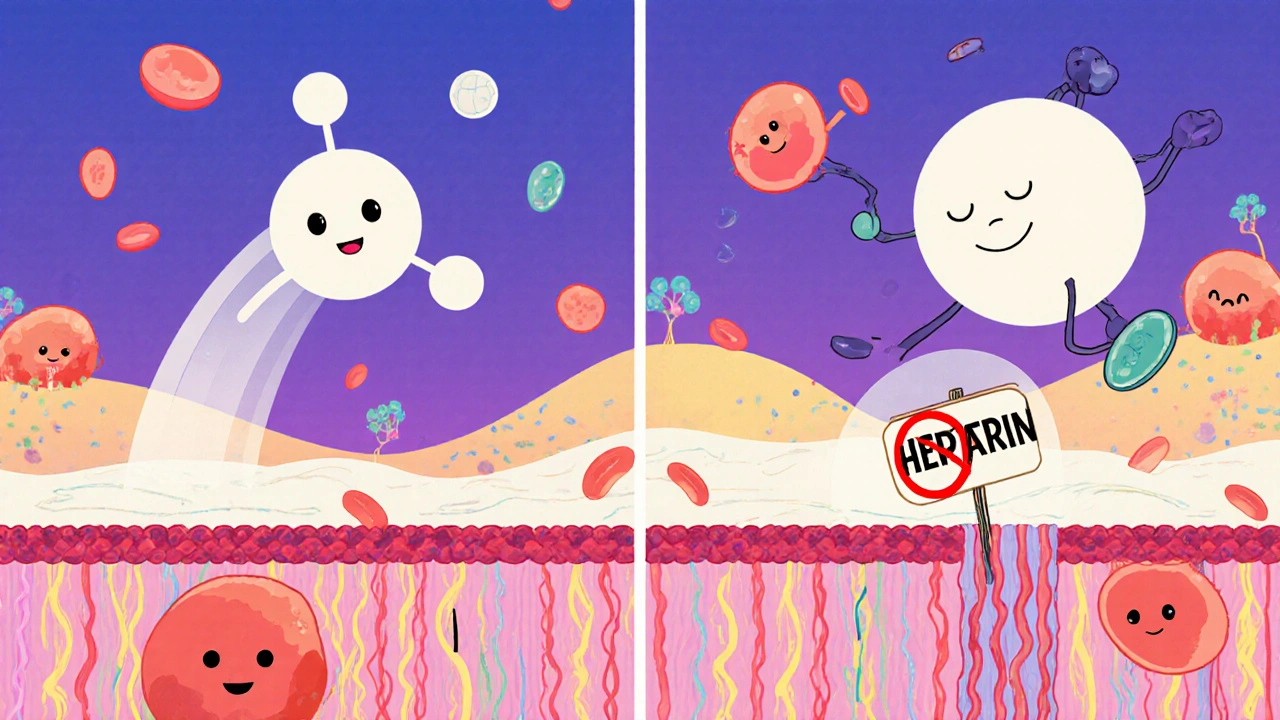

Medications don’t travel to breast milk by magic. They move through the body the same way nutrients do: from your bloodstream, through the walls of tiny blood vessels near the milk-producing glands, and into the milk itself. About 75% of this transfer happens through passive diffusion. That means the drug follows a simple rule: it moves from where it’s more concentrated (your blood) to where it’s less concentrated (your milk) until things balance out. The rest of the transfer - about 25% - happens through special protein channels in the cells that make milk. Some drugs, like nitrofurantoin or acyclovir, use these channels like a backdoor. This is why some medications end up in milk even when they shouldn’t based on size or solubility alone. Several factors determine how much of a drug ends up in your milk:- Molecular weight: Drugs heavier than 800 daltons (like heparin) barely get through. Lighter ones - under 300 daltons, like lithium - slip through easily.

- Lipid solubility: Fatty (lipophilic) drugs like diazepam cross cell membranes easily and end up in higher concentrations in milk. Water-soluble drugs like gentamicin barely make the trip.

- Protein binding: If a drug sticks tightly to proteins in your blood (like warfarin, which is 99% bound), it can’t float freely into milk. Even sertraline, which is 98.5% bound, still gets through - but only a little.

- pKa and pH trapping: Weak bases like amitriptyline (pKa 9.4) get trapped in milk because breast milk is slightly more acidic than blood. This can make milk concentrations 2 to 5 times higher than in your blood.

Timing Matters - When You Take the Pill Makes a Difference

It’s not just what you take - it’s when. Taking your medication right after you breastfeed gives your body time to clear most of it before the next feeding. Studies show this simple trick can reduce your baby’s exposure by 30-50%. For example, if you take an antidepressant like sertraline after the evening feeding, your baby gets the lowest possible dose during the night. For drugs with long half-lives - like diazepam, which can stay in a newborn’s system for up to 100 hours - timing becomes even more critical. A single dose right before bedtime can lead to days of low-level exposure. In these cases, doctors may recommend switching to a shorter-acting alternative like lorazepam.Not All Drugs Are Created Equal

The medical community has spent decades sorting drugs into safety categories. The most trusted system comes from the InfantRisk Center, which rates medications on a scale from 1 to 5:- Level 1: No detectable transfer. Examples: insulin, heparin, most antibiotics like amoxicillin and cephalexin.

- Level 2: Minimal transfer, no reported infant side effects. Examples: sertraline, acetaminophen, ibuprofen.

- Level 3: Limited data, possible mild effects. Use with caution. Examples: fluoxetine, some ADHD medications.

- Level 4: Possible risk. Avoid unless benefits outweigh risks. Examples: lithium, certain anticonvulsants.

- Level 5: Proven danger. Absolutely avoid. Examples: radioactive iodine-131, chemotherapy drugs.

What About Antidepressants and Psychiatric Drugs?

This is where most mothers panic. Depression and anxiety don’t disappear after birth - and untreated mental illness can be far more harmful to a baby than a low-dose antidepressant. Sertraline (Zoloft) is the most prescribed antidepressant during breastfeeding. Studies show infants receive only 1-2% of the mother’s weight-adjusted dose. Infant serum levels rarely exceed 10% of what’s considered therapeutic for adults. In a 2022 study, only 8.7% of babies exposed to sertraline showed mild irritability - and that often resolved on its own. Fluoxetine (Prozac), on the other hand, has a long half-life and builds up in milk. It’s linked to higher rates of colic, poor feeding, and sleep disturbances. For this reason, sertraline is preferred over fluoxetine for breastfeeding mothers. The European Medicines Agency warns about serotonin syndrome - a rare but serious reaction - but actual cases in breastfed infants are extremely rare. The bigger risk? Stopping your medication and relapsing into depression. That affects your ability to care for your baby far more than the drug ever could.What About Antibiotics, Painkillers, and Birth Control?

Antibiotics like amoxicillin, cephalexin, and clindamycin are almost always safe. Infant exposure is typically less than 1-3% of the maternal dose. Gentamicin, an injectable antibiotic, barely passes into milk at all - less than 0.1%. Pain relievers like acetaminophen and ibuprofen are also low-risk. They’re found in milk in trace amounts and have been used safely for decades. Avoid aspirin in high doses or long-term use - it can cause Reye’s syndrome in infants. Birth control is a different story. Combination pills with more than 50 mcg of ethinyl estradiol can slash your milk supply by 40-60% within 72 hours. That’s why progestin-only pills (the mini-pill) are the standard recommendation. Even then, some women notice a dip in supply - so it’s best to wait until your milk is well established (around 6 weeks postpartum) before starting.What Signs Should You Watch For?

Most babies show no reaction at all. But if you notice any of these, talk to your doctor:- Unusual sleepiness or difficulty waking to feed

- Poor feeding or refusal to latch

- Excessive fussiness or irritability

- Rash or diarrhea

- Jaundice that doesn’t improve

Special Cases: Nuclear Medicine and Vaccines

Some procedures need extra caution. A VQ scan (used to check for blood clots in the lungs) uses a radioactive tracer. Breastfeeding should be paused for 12-24 hours after this test. But an FDG-PET scan? You can keep breastfeeding. Only 0.002% of the dose ends up in milk - less than you’d get from eating a banana. Vaccines are safe. The flu shot, Tdap, and COVID-19 vaccines don’t contain live viruses. They can’t infect your baby through milk. In fact, antibodies from these vaccines do pass into milk - giving your baby extra protection.What to Do If You’re Worried

Don’t stop breastfeeding because you’re scared. Most medications are safe. If you’re unsure:- Check the InfantRisk Center’s LactMed app (version 3.2 or newer) - it’s updated monthly and uses real data from over 2,500 drugs.

- Ask your doctor or pharmacist to look up your medication using the Lactation Risk Categories (L1-L5).

- Time your doses to minimize exposure: take meds right after nursing.

- Watch your baby for subtle changes - not every cry means the drug is to blame.

- If you’re on a long-term medication, ask about therapeutic drug monitoring - a simple blood test can confirm your baby’s exposure is safe.

The Bigger Picture: Why This Matters

About 56% of breastfeeding mothers take at least one medication. Yet 42% stop breastfeeding within six months - and medication fears are the third most common reason, behind low milk supply and nipple pain. Here’s the truth: most of those women didn’t need to stop. A 2022 study found that 15-30% of breastfeeding cessations due to medication concerns were unnecessary. The risk from stopping breastfeeding - increased risk of infections, ear infections, obesity, and even sudden infant death syndrome - often outweighs the tiny risk from the drug. The FDA now requires all new drugs to include lactation data. The science is clearer than ever. You don’t have to choose between being a healthy mom and being a breastfeeding mom. You can be both.Do all medications pass into breast milk?

Almost all medications enter breast milk to some degree, but the amount is usually very small - often less than 1-2% of the mother’s dose. Heavy drugs like heparin, highly protein-bound drugs like warfarin, and water-soluble drugs like gentamicin transfer minimally. Most drugs pose no risk to the baby.

Is it safe to take antidepressants while breastfeeding?

Yes, many are. Sertraline (Zoloft) is the most studied and preferred option, with infant exposure at just 1-2% of the mother’s dose. Fluoxetine and paroxetine are less ideal due to longer half-lives and higher milk concentrations. Untreated depression poses a greater risk to infant development than these medications. Always consult your doctor before making changes.

Can I take ibuprofen or Tylenol while breastfeeding?

Yes. Both ibuprofen and acetaminophen (Tylenol) are considered safe. They pass into milk in very small amounts and have been used safely for decades. Avoid aspirin, especially in high doses or long-term use, due to the risk of Reye’s syndrome in infants.

When is the best time to take medication to protect my baby?

Take your medication right after breastfeeding. This allows your body time to clear the drug before the next feeding - reducing infant exposure by 30-50%. For drugs with long half-lives, spacing doses to avoid peak concentrations during feedings is key.

Do birth control pills affect breast milk supply?

Combination pills with high-dose estrogen (over 50 mcg ethinyl estradiol) can reduce milk supply by 40-60% within 72 hours. Progestin-only pills (mini-pills) are safer and recommended for breastfeeding mothers. Wait until breastfeeding is well established (around 6 weeks) before starting any hormonal birth control.

Should I pump and dump after taking medication?

Rarely. Pumping and dumping doesn’t speed up drug clearance from your body - only time does. Unless you’re taking a truly dangerous drug (like radioactive iodine), there’s no benefit to discarding milk. It can harm your supply and cause unnecessary stress. Always check with your provider before doing this.

What if my baby seems sleepy or fussy after I take medication?

Mild fussiness or sleepiness can happen, especially with benzodiazepines or SSRIs. But these symptoms are usually temporary and resolve on their own. Track the timing - does it happen right after you take the pill? If symptoms are severe or persistent, talk to your pediatrician. They can check infant blood levels if needed. Don’t assume it’s the medication - other causes like growth spurts or teething are more common.

Iska Ede

November 19, 2025 AT 03:40So let me get this straight - we’re now treating breastfeeding like a drug delivery system with a side of anxiety? 😂 I took ibuprofen after my kid’s 2am feed and now I’m supposed to time it like a rocket launch? Next they’ll tell me to wear a lab coat while nursing.

Also, who decided 1-2% is ‘safe’? My baby once sneezed and I panicked for a week. I’m just glad my meds aren’t radioactive.

Also also - I didn’t pump and dump. I just kept feeding. And my kid’s now 3 and still thinks bananas are the best thing since sliced bread. Coincidence? I think not.

Gabriella Jayne Bosticco

November 19, 2025 AT 15:39It’s wild how much fear surrounds something that’s naturally meant to be simple. Your body knows what to do - it’s the internet and the well-meaning strangers who turn it into a minefield.

I took sertraline for 8 months while nursing. My daughter slept through the night at 3 months, ate like a champ, and now she’s a little drama queen who demands snacks at 7am. No side effects. Just a happy kid and a mom who didn’t give up.

Don’t let fear steal your joy. You’re doing better than you think.

Sarah Frey

November 21, 2025 AT 14:14It is imperative to acknowledge that the scientific consensus regarding pharmacokinetic transfer into human milk has undergone rigorous peer review and is substantiated by longitudinal clinical data. The American Academy of Pediatrics, the World Health Organization, and the InfantRisk Center have collectively affirmed that the vast majority of commonly prescribed medications pose negligible risk to the nursing infant.

Furthermore, the cessation of breastfeeding due to unwarranted pharmacological concerns constitutes a public health issue of significant magnitude, as it correlates with increased incidence of infectious disease, metabolic dysregulation, and neurodevelopmental vulnerability in early infancy.

Therefore, clinicians and lactating individuals alike must prioritize evidence-based decision-making over anecdotal fear.

Katelyn Sykes

November 21, 2025 AT 21:17Y’all are overthinking this so hard

I took benzos and antidepressants and antibiotics and even a stupid migraine med and my kid is now a 5 year old who climbs trees and eats pickles for breakfast

Don’t panic. Don’t pump and dump unless your doc says so. Don’t let Reddit turn you into a nervous wreck

Also sertraline is the MVP. If your doc pushes fluoxetine? Ask for a second opinion. It’s not worth the colic.

And yes you can take ibuprofen. Yes you can. Just do it after you nurse. Done.

Love you moms. You’re not failing. You’re fighting.

Gabe Solack

November 23, 2025 AT 11:47This is such a needed post 🙌

My wife was on sertraline and we timed it like clockwork - right after the 10pm feed. Baby slept like a log. No fuss. No drama.

And yes - vaccines in milk? YES. Antibodies are basically your baby’s first superhero cape. 🦸♀️

Also - pump and dump is 99% unnecessary. You’re not flushing money down the toilet, you’re flushing peace of mind. Save the milk. Save your supply. Save your sanity.

Yash Nair

November 25, 2025 AT 01:56USA is full of weak moms who panic over pills. In India we breastfeed while taking ayurvedic herbs, turmeric paste, and chai with 3 sugars. Baby still grows like a tree. No doctors. No apps. Just mother instinct.

Why you need LactMed app? Just eat good food and cry less. Problem solved.

Also why you take so many pills? You are weak. You need yoga. You need god. Not science.

Bailey Sheppard

November 26, 2025 AT 20:08I just want to say - you’re not alone. I was terrified when I started my antidepressant. I read every study. I cried. I Googled until 3am.

But then I talked to my lactation consultant and she just said: ‘Your baby needs you more than they need you to be perfect.’

Turns out, she was right. My daughter is thriving. And I’m still here. That’s the win.

Heidi R

November 28, 2025 AT 13:28Of course you’re going to get drugs in your milk. That’s what happens when you let Big Pharma control your body. Did you know the FDA is owned by Pfizer? And they want you to keep breastfeeding so they can sell more pills to babies. Wake up.

I didn’t take anything. I breastfed for 18 months on pure love and organic kale. My child is now a genius. You’re welcome.

Brenda Kuter

November 29, 2025 AT 22:50MY BABY GOT A RASH AFTER I TOOK IBUPROFEN AND NOW THEY’RE A VEGAN ZOMBIE WHO HATES LIGHT AND ONLY CRIES IN THE DARK AND I THINK IT’S BECAUSE OF THE DRUGS AND I’M GOING TO BE A MOTHER ON A MISSION TO EXPOSE THIS CORRUPT MEDICAL INDUSTRY AND I’M STARTING A PETITION AND I NEED 10,000 SIGNATURES AND IF YOU DON’T SIGN YOU’RE A PART OF THE PROBLEM AND MY BABY ISN’T JUST SLEEPY SHE’S BEING POISONED AND I’M GOING TO CRY UNTIL THE SYSTEM CHANGES AND I HOPE YOU’RE HAPPY WITH YOUR LITTLE TINY PILLS AND YOUR LACTMED APPS AND YOUR FANCY DOCTORS WHO DON’T CARE ABOUT REAL MOTHERS

PS I’M NOT ON SOCIAL MEDIA ANYMORE BUT I’M STILL WATCHING YOU.

Shaun Barratt

December 1, 2025 AT 10:49It is a well-documented physiological phenomenon that pharmacological agents traverse the mammary epithelial barrier via passive diffusion, governed primarily by molecular weight, lipid solubility, and protein binding affinity. The clinical relevance of this transfer is, in the overwhelming majority of cases, negligible.

Furthermore, the temporal optimization of dosing relative to lactation events constitutes a clinically validated strategy for minimizing infant exposure. This approach is not anecdotal; it is pharmacokinetic.

One must, therefore, exercise discernment and avoid conflating anecdotal fear with evidence-based practice.

Girish Pai

December 2, 2025 AT 00:28Pharmacokinetic parameters are critical in lactation safety profiling. The volume of distribution (Vd) and clearance rate (CL) directly correlate with infant plasma concentration. For instance, sertraline’s low Vd and high protein binding result in milk concentrations below 0.5% of maternal dose - well below the threshold for pharmacological effect in neonates.

Meanwhile, fluoxetine’s long half-life (4-6 days) leads to accumulation - hence, it is contraindicated in neonates with immature CYP2D6 metabolism.

Bottom line: Don’t guess. Use pharmacokinetic modeling. Use LactMed. Use science.

Kristi Joy

December 2, 2025 AT 14:32Hey mama - you’re doing an incredible job just by asking this question.

It’s okay to be scared. It’s okay to need help. It’s okay to take a pill and still be a great mom.

I’ve been where you are. I cried in the pharmacy aisle because I didn’t know if I was hurting my baby.

You’re not broken. You’re not failing. You’re not alone.

And your baby? They’re lucky to have you - meds and all.

Hal Nicholas

December 2, 2025 AT 17:06Let me be the first to say it - most of you are just lazy. You want your meds and your Netflix and your breastfeeding. You don’t want to deal with the hard part: being present.

Real mothers don’t need apps. Real mothers don’t time their pills. Real mothers just… mother.

If your baby is fussy, maybe it’s not the drug. Maybe it’s you.

Just saying.

Louie Amour

December 3, 2025 AT 23:12Of course you’re going to get drugs in your milk. That’s what happens when you let the government tell you what’s safe. I’m not taking any of that crap. I’m doing a 30-day cleanse, drinking lemon water, and breastfeeding with my bare hands. My baby’s immune system is now stronger than yours.

Also, I don’t believe in science. I believe in crystals.

And if your baby has a rash? That’s just karma for using birth control.

Kristina Williams

December 4, 2025 AT 20:45Did you know that the FDA and Pfizer are working together to make moms feel guilty so they keep taking pills? I read it on a blog. My cousin’s friend’s neighbor’s dog got sick after its owner took ibuprofen. Now the dog is in a wheelchair. That’s why I only drink herbal tea and cry into my pillow. My baby is fine. But you? You’re poisoning your child. And you don’t even know it.