When your kidneys suddenly stop working right, it’s easy to blame dehydration, infection, or old age. But what if the culprit is something you took every morning for months-or even years? Acute interstitial nephritis (AIN) is one of the most common yet overlooked causes of sudden kidney failure, and it’s often triggered by everyday medications. Unlike a urinary tract infection or kidney stone, AIN doesn’t show up on routine urine tests. It doesn’t always cause pain. And in many cases, the signs are so vague that doctors miss it for weeks. By then, the damage may already be lasting.

What Actually Happens in Your Kidneys

Your kidneys are made up of millions of tiny filtering units called nephrons. Between these units is the interstitium-a space filled with connective tissue, blood vessels, and immune cells. In AIN, this area becomes inflamed. Immune cells swarm in, swelling the tissue, crushing the tubules, and blocking urine flow. The result? Your kidneys can’t filter waste, regulate fluids, or maintain electrolyte balance anymore. This isn’t a slow decline. It’s an abrupt drop in kidney function, often caught when blood tests show rising creatinine levels. The inflammation isn’t random. It’s almost always a reaction to a drug. About 60 to 70% of all AIN cases are caused by medications. That’s more than infections, autoimmune diseases, or electrolyte imbalances combined.The Top Drug Triggers (And Why They’re Surprising)

You might assume antibiotics are the biggest offender-and they are. Penicillins, cephalosporins, sulfonamides, and ciprofloxacin account for nearly one-third of cases. These drugs often cause a classic allergic reaction: fever, rash, joint pain, and eosinophils in the urine. But here’s the catch: less than 10% of people with AIN have all three signs. Most just feel tired, nauseous, or run down. The real surprise? Proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole, pantoprazole, and esomeprazole. These are among the most commonly prescribed drugs in the world. People take them for heartburn, acid reflux, or even as a precaution. But over the last decade, PPIs have become the second leading cause of AIN. In some recent studies, they’re responsible for nearly 40% of cases. And here’s the kicker: even though the inflammation from PPIs tends to be milder, recovery is worse. Only 50 to 60% of patients regain full kidney function after stopping the drug. NSAIDs like ibuprofen, naproxen, and celecoxib are the #1 cause in older adults. They make up 44% of drug-induced AIN cases. Unlike antibiotics, NSAIDs don’t usually cause rashes or fever. Instead, they cause heavy protein loss in the urine-sometimes enough to look like nephrotic syndrome. These cases often develop slowly, after months or even years of use. By the time someone sees a doctor, the kidneys are already damaged. Even newer drugs like immune checkpoint inhibitors (used in cancer treatment) are now linked to AIN. These drugs work by turning up the immune system, but sometimes they turn it up too high-attacking the kidneys by mistake.Why Diagnosis Takes So Long

Most patients don’t realize something’s wrong until their creatinine is sky-high. The symptoms? Fatigue, nausea, loss of appetite, low-grade fever. These look like the flu, a stomach bug, or just aging. Many end up in the ER thinking they have a urinary tract infection-only to find out their kidneys are failing. Doctors rarely think of AIN unless they’re told about recent drug use. Even then, urine tests for eosinophils or gallium scans are unreliable. The only sure way to diagnose it? A kidney biopsy. That means a needle through the back, under local anesthesia, to pull out a tiny piece of tissue. It’s invasive. It’s scary. But it’s necessary. One patient story from the American Kidney Fund tells of a 63-year-old woman who took omeprazole for 18 months. She felt tired. Her legs swelled. She was told she had “fluid retention.” After three weeks of dialysis, a biopsy confirmed AIN. Her kidneys never fully recovered. Her eGFR dropped to 45 and stayed there a year later.

Recovery: It’s Not Guaranteed

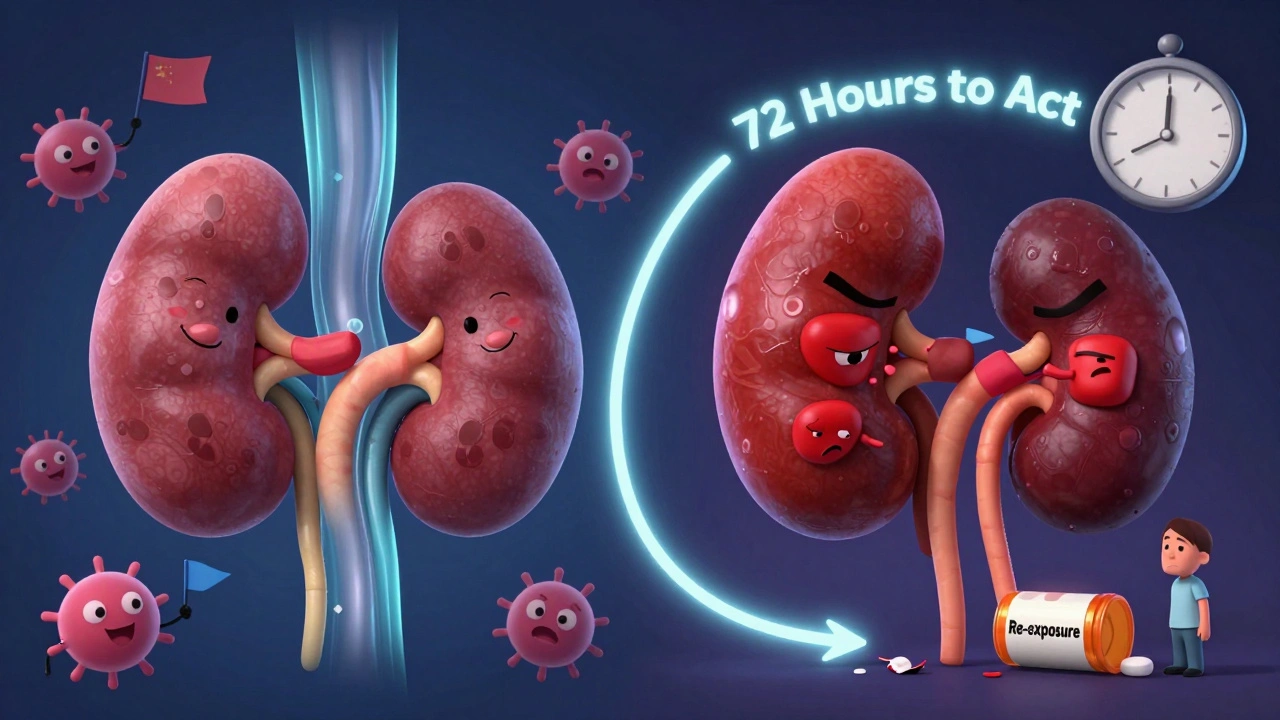

The first and most important step? Stop the drug. Right away. If you’re on a PPI, NSAID, or antibiotic and your kidney function drops, don’t wait for a biopsy. Stop the medication. Most guidelines say to do it within 24 to 48 hours of suspicion. After stopping the drug, some people start feeling better in 72 hours. In one survey of 120 patients, 65% saw improvement within three days. But that doesn’t mean they’re cured. Recovery time depends on the drug:- Antibiotics: median recovery in 14 days

- NSAIDs: median recovery in 28 days

- PPIs: median recovery in 35 days

Do Steroids Help?

This is where things get messy. There’s no solid proof from randomized trials that steroids like prednisone or methylprednisolone improve outcomes. But doctors use them anyway. Why? Because in severe cases-when eGFR drops below 30, or when kidney function keeps worsening after stopping the drug-steroids seem to help. The typical protocol: methylprednisolone at 0.5 to 1 mg per kg of body weight for 2 to 4 weeks, then a slow taper over 6 to 8 weeks. The European Renal Association says there’s no perfect dose. The American Society of Nephrology says early treatment matters more than the exact number. One expert put it bluntly: “If you wait too long, steroids won’t help. The damage is already done.”

Who’s at Highest Risk?

Age is a big factor. People over 65 are nearly five times more likely to develop AIN than those under 45. Why? Because they’re more likely to be on multiple medications. Polypharmacy-taking five or more drugs-raises your risk by 3.2 times. Women over 65 on PPIs? That’s the highest-risk group. PPIs are often prescribed long-term without clear benefit. Many people take them for years, thinking they’re harmless. But the data shows: for every 100,000 people on PPIs, about 12 will develop AIN each year.What You Can Do

If you’re on any of these drugs and notice new fatigue, swelling, nausea, or decreased urine output:- Check your recent meds. Did you start a new drug in the last 30 days? Even if it’s “over-the-counter,” like ibuprofen or omeprazole.

- Ask your doctor for a creatinine test and eGFR calculation. Don’t wait for symptoms to get worse.

- If your kidney function is dropping, don’t assume it’s “just aging.” Push for a drug review.

- If you’ve had AIN before, avoid the triggering drug forever. Re-exposure can cause worse damage.

What’s Next for AIN?

Researchers are hunting for a blood or urine test that can replace the biopsy. One promising marker, urinary CD163, detected AIN with 89% accuracy in a 2022 study. If it’s validated, we could diagnose AIN without surgery. Meanwhile, the FDA has issued warnings about PPIs and kidney damage. But prescriptions keep rising. So do cases. Experts predict a 15% increase in AIN by 2025 if nothing changes. The bottom line? Medications are powerful. Even common ones. What feels like a harmless pill for heartburn could be quietly damaging your kidneys. Pay attention. Ask questions. And if something feels off, don’t wait.Can acute interstitial nephritis be reversed?

Yes, in many cases-if caught early. Stopping the triggering drug within days of symptom onset gives you the best chance. About 70-80% of patients recover most or all kidney function, especially if antibiotics caused the AIN. But if the damage is advanced or the drug was taken for months (like PPIs or NSAIDs), recovery is incomplete. Up to 30% of patients develop permanent chronic kidney disease.

Which drugs are most likely to cause acute interstitial nephritis?

The top three are proton pump inhibitors (PPIs) like omeprazole, NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen, and antibiotics such as penicillins and sulfonamides. PPIs are now the second most common cause, despite being considered low-risk. NSAIDs are the leading cause in older adults, and antibiotics often trigger the classic allergic reaction with fever and rash.

Do I need a kidney biopsy to diagnose AIN?

Yes, it’s the only definitive test. Blood tests, urine tests, and imaging can suggest AIN, but they can’t confirm it. A biopsy shows immune cells and inflammation in the kidney tissue-proof that it’s AIN and not another kidney disease. While researchers are testing new biomarkers, biopsy remains the gold standard.

Can I take NSAIDs again after having AIN?

No. Re-exposure to the drug that caused your AIN-even years later-can trigger a more severe reaction and faster kidney damage. If you’ve had NSAID-induced AIN, avoid all NSAIDs permanently. Use acetaminophen instead for pain or fever. Always check with your doctor before starting any new pain reliever.

How long does it take to recover from AIN?

Recovery time depends on the drug. Antibiotic-induced AIN often improves in about 14 days after stopping the drug. NSAID-induced cases take closer to 28 days. PPI-induced AIN can take 35 days or longer. Full recovery may take months. If kidney function doesn’t improve within 72 hours of stopping the drug, steroid treatment may be considered.

Is acute interstitial nephritis common?

It’s not rare. AIN causes 5-15% of all acute kidney injury cases in hospitals. Drug-induced AIN is the most common form. With rising PPI use, cases have increased by 27% since 2010. An estimated 12 cases occur per 100,000 people each year from PPIs alone. Older adults and those on multiple medications are at highest risk.

Eric Vlach

December 2, 2025 AT 00:53Been on omeprazole for years because my job stresses me out and I eat junk constantly. Never thought it could mess with my kidneys. Now I’m scared to stop it but also scared to keep taking it. What do I do?

Souvik Datta

December 2, 2025 AT 18:08There’s a deeper truth here - we treat medicine like candy. We pop pills like they’re M&Ms without asking what they’re doing to our bodies. The body doesn’t lie. If your kidneys are whispering for help, don’t wait for them to scream.

Irving Steinberg

December 4, 2025 AT 11:40So basically if you’re over 50 and take Tums or Advil you’re basically doing slow-mo kidney suicide 😅

Lydia Zhang

December 5, 2025 AT 15:09My mom had this. She didn’t even know she was sick until she passed out.

Kay Lam

December 5, 2025 AT 15:54I’ve been a nurse for 22 years and I’ve seen this over and over. People come in with creatinine at 5.8 and say they’ve been taking ibuprofen for their back pain since last Christmas. They don’t think it’s a big deal. But kidneys don’t bounce back like your ankle after a sprain. Once the scarring starts, it’s permanent. And no, you can’t just ‘drink more water’ and fix it. It’s not a hangover. It’s your nephrons dying. And the worst part? Doctors don’t even test for it unless you specifically ask. They assume it’s dehydration or diabetes. I’ve had patients on PPIs for 10 years and never once had their kidney function checked. That’s not negligence - that’s systemic ignorance.

Courtney Co

December 7, 2025 AT 06:21Wait so you’re telling me my daily Prilosec is slowly killing me? I’ve been taking it since 2017. I’m 58. I’m gonna die because I didn’t want to feel heartburn? This is a trap. I feel like I’ve been gaslit by Big Pharma.

Priyam Tomar

December 7, 2025 AT 11:38Actually, most of these cases are preventable - if people weren’t so lazy. You don’t need a biopsy to know something’s wrong. Check your labs. Stop blaming the drug. Blame yourself for not monitoring your health. And don’t even get me started on people taking NSAIDs like they’re vitamins.

Matt Dean

December 8, 2025 AT 10:03Anyone else notice how every time a drug gets flagged for kidney damage, the FDA just issues a tiny warning buried in the fine print? Meanwhile, the ads keep running. PPIs are everywhere. It’s not an accident. It’s profit.

Bee Floyd

December 9, 2025 AT 13:58My uncle had AIN after 5 years of naproxen for arthritis. He’s on dialysis now. He never felt pain. Just… tired. Like he was running on low battery. No one told him to get his creatinine checked. He thought he was just getting old. This isn’t just medical - it’s a cultural failure. We’ve normalized ignoring our bodies until they break.

Jeremy Butler

December 10, 2025 AT 12:24It is of paramount importance to underscore that the pathophysiological cascade precipitated by pharmacological agents in the context of acute interstitial nephritis is both insidious and multifactorial, involving T-cell-mediated immune dysregulation and cytokine-driven tubulointerstitial infiltration, which may remain clinically silent until renal functional reserve is critically depleted.

Shashank Vira

December 11, 2025 AT 01:35How dare they make us take pills like they’re harmless? We’re not lab rats. We’re sentient beings who deserve to know the quiet, slow violence of modern medicine. This isn’t just a medical condition - it’s a tragedy of modernity.

Jack Arscott

December 12, 2025 AT 07:44Just stopped my PPI last week after reading this. Fingers crossed 🤞

Walker Alvey

December 13, 2025 AT 07:39Wow so people are still surprised drugs can have side effects? What planet are you from? Next you’ll tell me smoking causes cancer.

Adrian Barnes

December 14, 2025 AT 11:59The real issue here isn’t the drugs - it’s the lack of accountability. Doctors prescribe without monitoring. Pharmacies sell without warning. Patients consume without questioning. This isn’t a medical crisis. It’s a moral one.

Jaswinder Singh

December 14, 2025 AT 22:27Bro I got AIN from ibuprofen. Took 2 years to get my kidneys back to 60%. I don’t take NSAIDs anymore. Ever. And I tell everyone I know. You think you’re being smart taking painkillers every day? You’re just gambling with your organs.